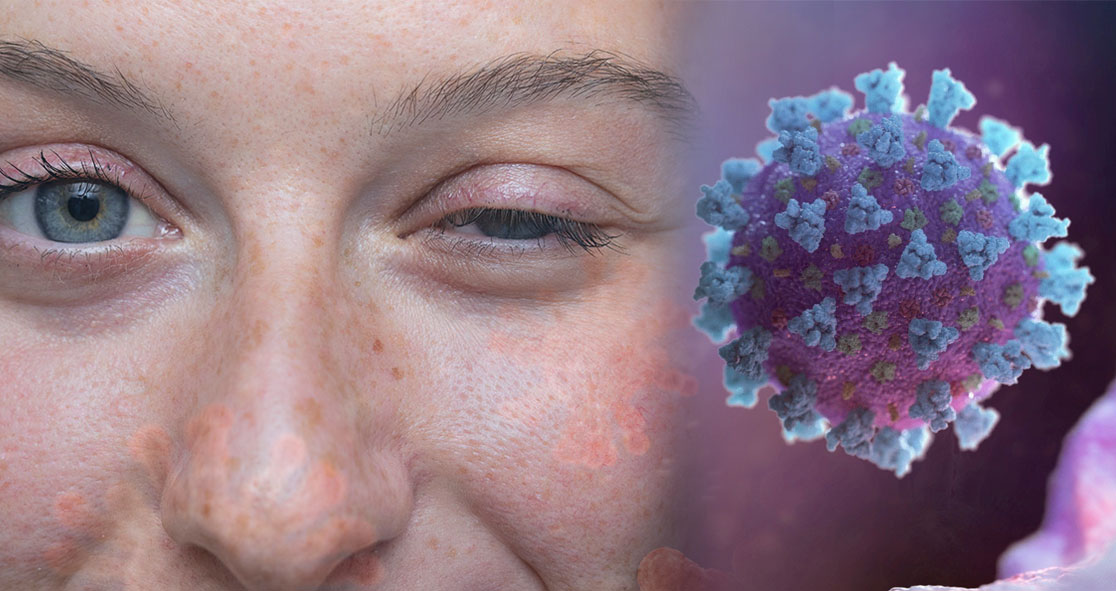

New research, published online last week in the Annals of Internal Medicine, has suggested that Myasthenia Gravis (MG) should be added to the growing list of potential neurological complications linked to COVID-19, the infection caused by the new coronavirus.

Italian clinicians reported three cases of acetylcholine receptor (AChR) antibody-positive MG after coronavirus infection.

Lead researcher Dr. Domenico Restivo of Garibaldi Hospital, Catania, Italy, told Medscape Medical News, “I think it is possible that there could be many more cases.”

“In fact, myasthenia gravis could be underestimated especially in the course of COVID-19 infection in which a specific muscular weakness is frequently present,” he added. “For this reason, this association is easy to miss if not top of mind.”

The three patients had no previous neurologic or autoimmune disorders. However, they developed the symptoms of MG within 5 to 7 days of fever caused by COVID-19 infection.

The authors noted that the time from presumed COVID-19 infection to MG symptoms “is consistent with the time from infection to symptoms in other neurologic disorders triggered by infections.”

The first patient, aged 64, had a fever as high as 102.2° F for 4 days. He developed diplopia (double vision) and muscle fatigue five days after the onset of fever. His neurologic examination was “unremarkable.” His CT thorax excluded thymoma and chest X-ray was normal.

The patient tested positive for COVID-19 on the nasal swab and real-time PCR tests. Analyzing his new symptoms, the researchers suspected myasthenia gravis. The investigator wrote that he was treated with pyridostigmine bromide and prednisone and had a response “typical for someone with myasthenia gravis.”

The second patient, a 68-year-old man, developed diplopia, muscle fatigue, and dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) after seven days of the onset of fever. Like the first patient, his chest CT and neurologic exam were normal, and he was tested positive through nasal swab and RT-PCR testing. The patient improved after receiving one cycle of I.V. immunoglobulin treatment.

The third patient, a 71-year-old woman, also developed diplopia, along with bilateral ocular ptosis (drooping of the upper eyelid) and hypophonia (soft speech), after five days of cough and fever. Her CT thorax excluded thymoma but showed bilateral interstitial pneumonia. After 6 days, she developed dysphagia and respiratory failure, requiring mechanical ventilation.

She improved after receiving plasmapheresis treatment and was eventually off ventilation.

The researchers wrote the findings in these three patients are “consistent with reports of other infections that induce autoimmune disorders, as well as with the growing evidence of other neurologic disorders with presumed autoimmune mechanisms after COVID-19 onset.”

“Antibodies that are directed against SARS-CoV-2 proteins may cross-react with AChR subunits because the virus has epitopes that are similar to components of the neuromuscular junction; this is known to occur in other neurologic autoimmune disorders after infection,” they added. “Alternatively, COVID-19 infection may break immunologic self-tolerance.”

Dr. Restivo said, “The main message for clinicians is that myasthenia gravis, as well as other neurological disorders associated with autoimmunity, could occur in the course of SARS-CoV-2 infection.” Recognizing the disease as soon as possible “could lead to a drug treatment that limits its evolution as quickly as possible,” he added.